Satelitski snimci Dinarskog gorja

|

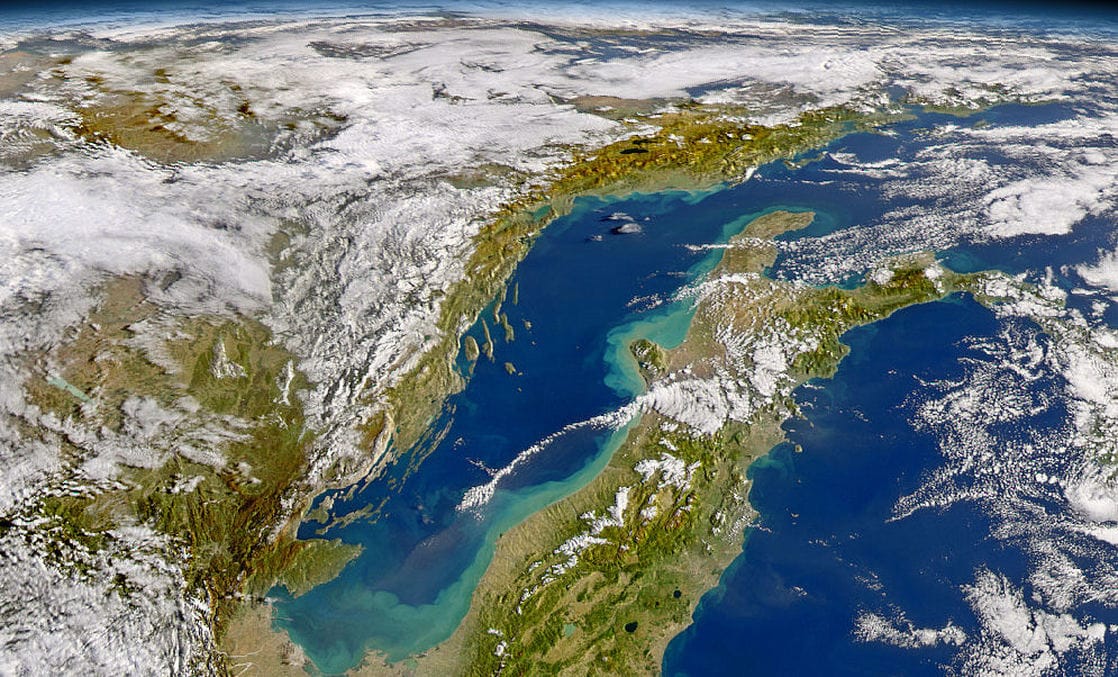

Nakon oluje

U dane 13. i 14.11.2004. preko Mediterana prošla je intenzivna oluja. Olujni vjetrovi potopili su pred obalom Alžira tri broda, a obilne kiše poplavile su dijelove zemlje. Preko noći oluja se preselila prema sjeveru, prema Italiji i Jadranu, gdje je zaustavila zračni, cestovni i morski promet, a naleti vjetra dosezali su brzine do 200 kilometara na sat - prema izvješćima lokalnih medija. Kako je oluja 15.11. nastavila svoj put Europom u smjeru istoka, ostavila je mnoga mjesta bez električne energije, u Hrvatskoj i obali Jadrana te u Rumunjskoj, gdje je palo više od 50 cm snijega. Dva dana kasnije, nebo se dovoljno očistilo kako bi omogućilo senzorima (SeaWiFS) na satelitu OrbView-2 satelita, ovako jasan pogled na Jadransko more. Nakon oluje, vode na talijanskoj obali Jadrana poprimile su mliječno zelenu boju jer su valovi pokretani vjetrom uzburkli vodu i izbacili sedimente s morskog dna prema površini. Daljnji dokaz oluje može se vidjeti u planinama Hrvatske i Bosne i Hercegovine, koje su prekrivene snijegom. Fotografija je snimljena 17.11.2004. Izvor: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=5010 |

After the storm

An intense winter storm raced across the Mediterranean on November 13 and 14, 2004. Gale-force winds sank three ships off Algiers, Algeria, and heavy rain drenched the country. Overnight, the storm moved north to Italy and the Adriatic Sea. Here, the storm halted air, road and sea traffic with winds that gusted up to 200 kilometers per hour (125 mph), according to local media reports. As it swept east across Europe on November 15, the storm cut off power and damaged communities in Croatia on the Adriatic coast and in Romania, where more than 50 centimeters (18 inches) of snow fell. Two days later, the clouds had cleared enough to give the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view (SeaWiFS) Sensor aboard the OrbView-2 satellite this clear view of the Adriatic Sea. In the wake of the storm, the waters along the Italian coastline are a milky green where the wind-tossed waves have churned the water, bringing sediment from the sea floor to the surface. Further evidence of the storm can be seen in the mountains of Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which are capped with snow. SeaWiFS obtained this image on November 17, 2004. Source: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=5010 |

|

Satelitski snimak Hrvatske i Bosne i Hercegovine iz 2003. godine

Izvor: NASA |

|

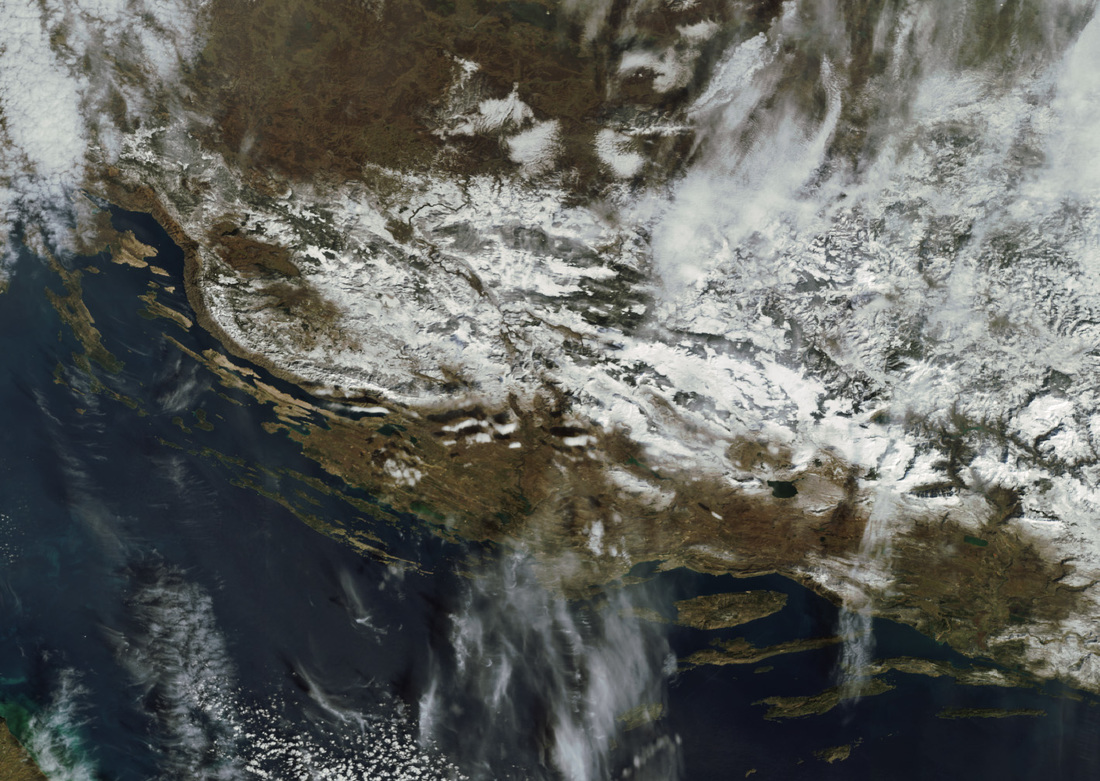

Stjenovita obala i otoci u Hrvatskoj i planine u zapadnoj Bosni

Snimljeno: 26.2.2009. Hrvatska je srednjoeuropska zemlja na raskrižju između Panonske nizine, jugoistočne Europe i Mediterana. Hrvatska graniči sa Slovenijom i Mađarskom na sjeveru, Srbijom na sjeveroistoku, Bosnom i Hercegovinom na istoku, a Crnom Gorom na krajnjem jugoistoku. Njezini južni i zapadni bokovi nalaze se na Jadranskom moru, i ona također dijeli morsku granicu s Italijom u Tršćanskom zaljevu. Njezin teren je raznolik, uključujući i ravnice, jezera i brežuljke na kontinentalnom sjeveru i sjeveroistoku (središnja Hrvatska i Slavonija, dio Panonske nizine), vidljivo na vrhu. Prema središtu, teren se sastoji od gusto pošumljenih planina u Lici i Gorskom kotaru, dijelovima Dinarskog gorja, prekrivene snijegom na slici, kao i planine na zapadu Bosne. Konačno, teren uključuje stjenovitu obalu na Jadranu (Istra, Sjeverna obala i Dalmacija), vidljivo u različitim nijansama smeđe boje prema dnu. Mnogi otoci također može vidjeti sa stjenovite obale, jer se u Hrvatskoj nalazi više od tisuću otoka različitih veličina. Najveći otoci u Hrvatskoj su Cres i Krk, koji se nalaze na sjevernm dijelu Jadranskog mora. Izvor fotografije i opisa: Earth napshot |

The Rocky Coast and Offshore Islands of Croatia and mountains in western Bosnia

Croatia - February 26th, 2009 Croatia is a Central European country at the crossroads between the Pannonian Plain, Southeast Europe, and the Mediterranean Sea. Croatia borders with Slovenia and Hungary to the north, Serbia to the northeast, Bosnia and Herzegovina to the east, and Montenegro to the far southeast. Its southern and western flanks border the Adriatic Sea, and it also shares a sea border with Italy in the Gulf of Trieste. Its terrain is diverse, including plains, lakes and rolling hills in the continental north and northeast (Central Croatia and Slavonia, part of the Pannonian Basin), visible at the top. Towards the center, the terrain consists of densely wooded mountains in Lika and Gorski Kotar, part of the Dinaric Alps, covered with snow in the image, as are the mountains in the western Bosnia. Finally, the terrain includes rocky coastlines on the Adriatic Sea (Istria, Northern Seacoast and Dalmatia), visible in varying shades of brown towards the bottom. Many islands can also be seen off the rocky coasts, as offshore Croatia consists of over one thousand islands varying in size. The largest islands in Croatia are Cres and Krk, which are located in the Adriatic Sea. Source and description: Earth Snapshot |

|

BIOKOVO

Masiv Biokova u Hrvatskoj dio je Dinarskog gorja koji se proteže duž obale Jadranskog mora. Samo Biokovo je park prirode, a obližnji grad Makarska, koji se nalazi između planina i mora, je popularno turističko odredište. Najviši vrh masiva je Sveti Jure na 1762 m. Biokovo se uglavnom sastoji od vapnenačkih stijena, nastalih u relativno toplim, plitkim vodama. Kasniji tektonski procesi podižu tu podlogu i karbonatne stijene nagriza erozija, što vodi do stvaranja prepoznatljivog reljefa poznatijeg kao krški reljef. Izvor i opis: NASA. The Biokovo Range in Croatia is part of the Dinaric Alps that extend along the coastline of the Adriatic Sea. The range itself is a nature park and the nearby city of Makarska, located between the mountains and the sea, is a popular tourist destination. The highest peak in the range is Sveti Jure at 1,762m. The Biokovo Range mainly comprises limestone rocks, deposited in relatively warm, shallow waters. Later tectonic processes lifted and exposed the carbonate rocks to erosion, leading to a distinctive surface known as karst topography.

Source and description: NASA |

|

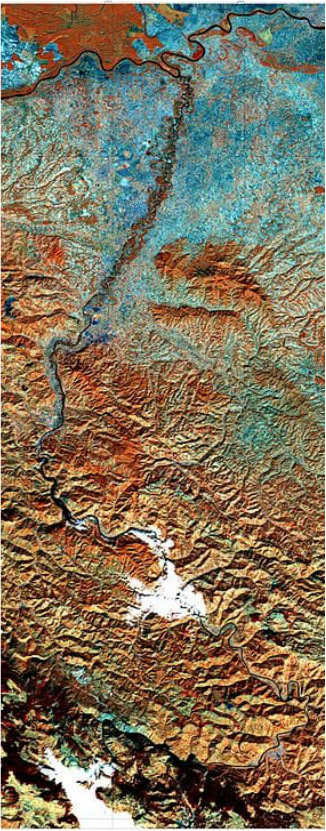

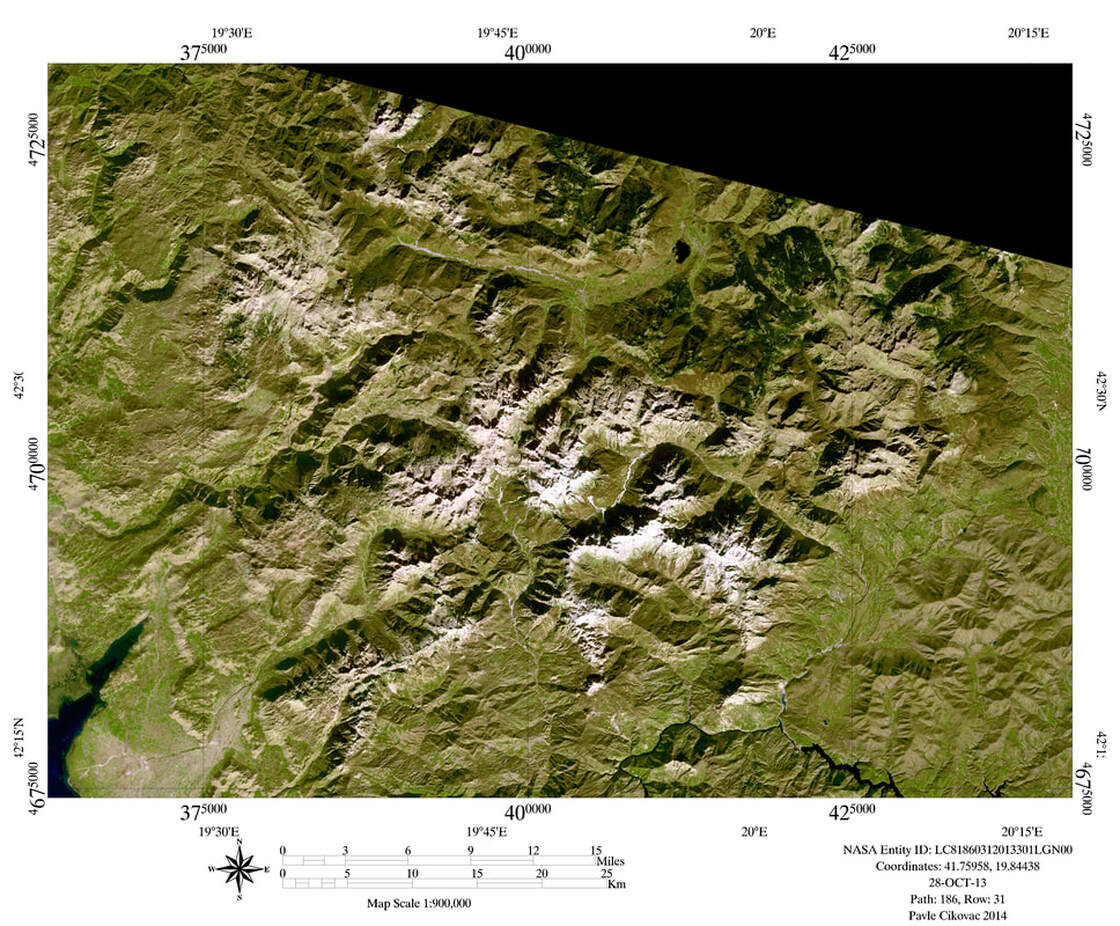

Dinarske planine prate dugu hrvatsku obalu Jadrana poput vijugave kralježnice. U zaleđu obale u Hrvatskoj planine dosižu 1831 metara visine (Dinara-Sinjal) i njihove gole strane pružaju dramatičnu pozadinu priobalnim hrvatskim turističkim mjestima. One također razdvajaju dvije klimatske zone u zemlji. Zapadno od planina, blage zime i suha ljeta mediteranske klime prevladavaju na obali. Na istočnoj strani planina, na visoravnima, nalaze se najhladnija i najvlažnija područja u Hrvatskoj.

Na ove dvije snimke koje su napravljene uređajem Operational Land Imager (OLI) na satelitu Landsat 8, može se vidjeti koja je uloga dinarskih planina u "upravljanju" vlagom. Snimke prikazuju sjeverozapadnu dalmatinsku obalu i Velebit. Na slici iz 11.12.2013., zeleno zaleđe Like vidljivo je istočno od Velebita. Na snimci od 27.10.2014. vidljivo je kako je masa Velebita "zarobila" guste oblake koji pokrivaju cijelo kontinentalno, ličko područje. Lika prima gotovo 1600 milimetara kiše godišnje, što omogućuje bujnu vegetaciju, pr. guste šume bukve i jele. Na suhoj, zapadnoj stani planine ("gdje rastu masline"), prevladva vegetacija mediteranskih šikara. Dinarske planine također utječu na lokalu klimu modificirajući zračne mase i oblikujući vjetrove. Kao i kod mnogih drugih naroda uz mediteranske obale, i obalni Hrvati imaju imena za sve vjetrove. Najpoznatiji i najžešći od njih je i bura (ili bora na stranim jezicima). Bura je vjetar na refule (zapuhe, nalete), nasilan, sjeveroistočni vjetar koji puše s obalnih planina prema Jadranu. U najgorim slučajevima, bura može dosegnuti brzinu i snagu uragana od 70 metara u sekundi (230 km na sat) i poremetiti živote obalnih stanovnika za nekoliko dana. Meteorolozi/klimatolozi su ranije smatrali kako je bura vjetar uvjetovan padanjem zračnih masa prema obali uz utjecaj topografije terena i pokretan temperaturnim razlikama. No, studije proteklih 40-ak godina ukazale su kako su se najsnažniji vjetrovi stvarali zbog pojave loma valova - rotacijskih turbulencija koje su se stvarale kada su se na svome putu prema obali Jadrana hladne zračne mase dolazile sa sjevera ili sjeveroistoka i nailazile na planinsku prepreku okomitu na tok zraka. Još 1889. godine, hrvatski meteorolog i seizmolog Andrija Mohorovičić prvi put je objavio zapažanja o ovoj vrsti turbulencije. Oblaci se samo ponekad pojavljuju uz buru, a tzv. "škura bura" (tamna) s oblacima je mnogo rjeđa nego bez oblaka ili "jasna bura". |

The Dinaric Alps follow Croatia’s long Adriatic coast like a curving spine. Reaching heights up to 1,831 meters tall (6,007 feet), the mountains and their bare leeward cliffs provide a dramatic backdrop to coastal Croatian vacation spots. They also divide two of the country’s climatic zones. West of the mountains, the mild winters and dry summers of a Mediterranean climate reign on the coast. On the windward east side, the country’s coldest and wettest places are found in the Croatian Highlands.

In this pair of images from the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, you can see the role that the Dinaric Alps play in managing moisture. The images show the northwestern Dalmatian coast and the Velebit Mountain Range. In the image from December 11, 2013, the green hinterlands of the Lika region are visible just east of the mountains. On the October 27, 2014, dense clouds are trapped by the Velebit Mountains and cover the region. The Lika region receives as much as 1,600 millimeters (63 inches) of rain per year, supporting dense forests of beech and fir trees. On the drier, “olive-climate” west side of the mountains, Mediterranean shrublands are most common.4 The Dinaric Alps also affect the local climate by shaping wind patterns. As with many people along Mediterranean shores, coastal Croatians have names for every wind. The most famous and furious of these is the bora (or bura in Croatian). The bora is a gusty, violent, northeasterly wind that whips down the Dinaric Alps and blows into the Adriatic. At its worst, the bora can reach hurricane-force speeds of 70 meters per second (156 miles per hour) and disrupt the lives of coastal residents for several days. Meteorologists previously thought the bora was a topographically descending, temperature-driven wind. But in studies over the past 40 years, they have discovered that the most severe winds are created by mountain wave breaking—the rotational turbulence created when airstreams are interrupted by mountain tops. As early as 1889, the Croatian meteorologist and seismologist Andrija Mohorovičić first published observations on this type of turbulence (the bora rotor cloud). Clouds only sometimes appear with the bora, and the so-called “dark bora” is much less common than the cloudless or “clear bora.” Source: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Laura Rocchio. Special thanks to the team at MapBox for tipping us off to the October 2014 image. Instrument(s): Landsat 8 - OLI |

|

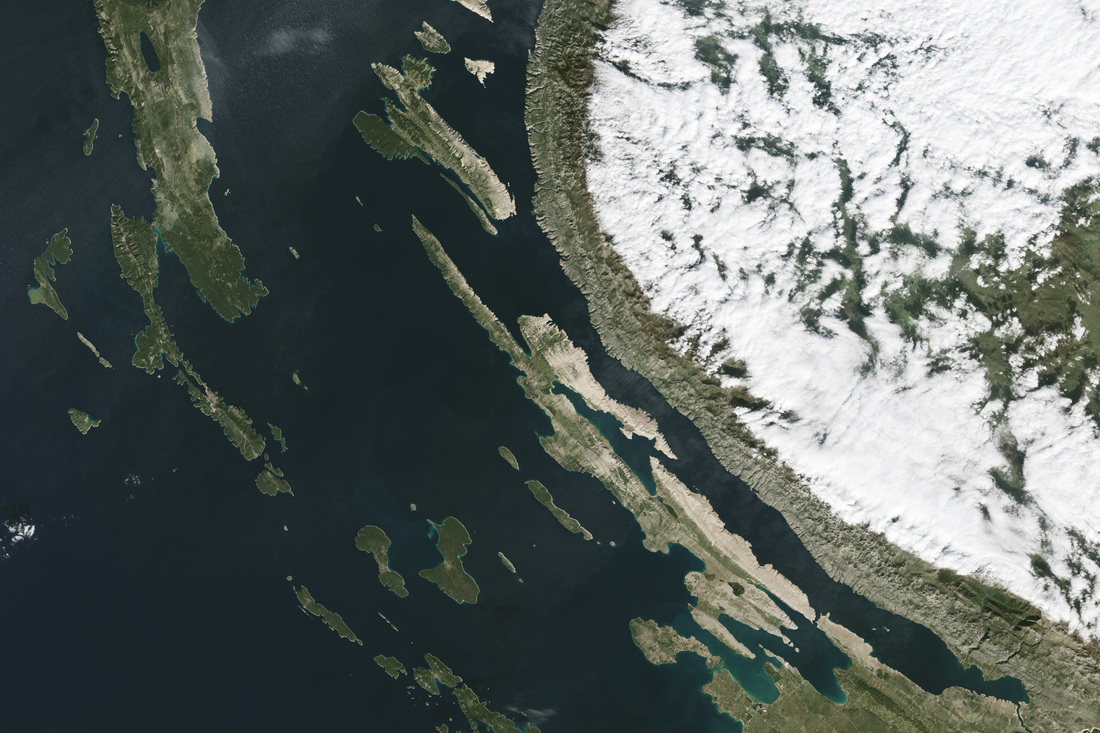

The largest lake on the Balkan Peninsula is colored by sediments eroded from the surrounding highlands.

Image of the Day for May 31, 2020 Instrument: ISS — Digital Camera Dark and light sediments swirl around in the center of Lake Skadar, the largest lake on the Balkan Peninsula. This pattern captured the attention of an astronaut onboard the International Space Station (ISS). Lake Skadar is a karst lake that straddles the border of Montenegro and Albania. It is an example of a cryptodepression, where parts of the lakebed extend below sea level. The curved, spine-like ridges running parallel with the southern shore are part of the Dinaric Alps, which are comprised mostly of easily erodible rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and other carbonates. The swirling plume in the center of the lake is likely the mixing of sediment that has been transported downstream from higher elevations via snow-melt water and other mountain runoff. A major source of this sediment inflow comes from the Moraca River; its wide delta occupies much of the Montenegro shoreline. Smaller river deltas along the northern edges of the lake also contribute sediment. The Drin River and the Bojana River converge just south of the ancient lake-front city of Shkodër, which lies on the small delta of the Kir River. The lake and these rivers all ultimately drain into the Adriatic Sea. As with many large freshwater lakes near cities, many of the native plants and animals in Lake Skadar became endangered due to human activity. Montenegro has since made the western portion of the lake a national park, and Albania declared its section as a nature reserve. Both efforts were made to protect many species of birds, microorganisms, and aquatic life, including eels, snails, and endemic fish species. Astronaut photograph ISS062-E-40353 was acquired on February 21, 2020, with a Nikon D5 digital camera using a 400 millimeter lens and is provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center. The image was taken by a member of the Expedition 62 crew. The image has been cropped and enhanced to improve contrast, and lens artifacts have been removed. The International Space Station Program supports the laboratory as part of the ISS National Lab to help astronauts take pictures of Earth that will be of the greatest value to scientists and the public, and to make those images freely available on the Internet. |

Najveće jezero na Balkanskom poluotoku obojeno je sedimentima erodiranim iz okolnog gorja.

Fotografija dana 31.5.2020 Instrument: ISS (Međunarodna svemirska stanica) - Digitalna kamera Tamni i svijetli sedimenti kovitlaju se u središtu Skadarskog jezera, najvećeg jezera na Balkanskom poluotoku. Ova pojava privukla je pažnju astronauta Međunarodne svemirske stanice (ISS). Skadarsko jezero je krško jezero koje se proteže na granici Crne Gore i Albanije. To je primjer kriptodepresije, gdje se dijelovi dna jezera protežu ispod razine mora. Zakrivljeni grebeni slični kralježnici koji teku paralelno s južnom obalom dio su Dinarskog gorja koje se sastoji od većinom lako erodivih stijena poput vapnenca, dolomita i drugih karbonata. Kovitlajuća smasa u središtu jezera vjerojatno je poslijedica miješanja sedimenata koji se ispiru nizvodno s viših nadmorskih visina vodom koja potječe od otapanja snijega i drugih planinskih otjecanja. Glavni izvor ovog dotoka sedimenata dolazi iz rijeke Morače; njezina široka delta zauzima velik dio obale jezera u Crnoj Gori. Manje delte rijeka uz sjeverne rubove jezera također doprinose nanošenju sedimaennta. Rijekr Drim i Bojana konvergiraju se južno od drevnog grada na jezeru Skadra (Shkodër), koji leži na maloj delti rijeke Kir. Jezero i ove rijeke u konačnici se slijevaju u Jadransko more. Kao i kod mnogih velikih slatkovodnih jezera u blizini gradova, mnoge su domaće biljke i životinje na Skadarskom jezeru postale ugrožene zbog ljudske aktivnosti. Crna Gora je zapadni dio jezera učinila nacionalnim parkom, a Albanija je svoj dio proglasila prirodnim rezervatom. Oba s ciljem zaštite mnogih vrsta ptica, mikroorganizama i vodenog života, uključujući jegulje, puževe i endemske vrste riba. Fotografija astronauta ISS062-E-40353 je snimljena 21.2.2020., digitalnim fotoaparatom Nikon D5 koji koristi objektiv veličine 400 milimetara, a koriste ga ISS Crew Earth Observation Facility i arth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center. Sliku je snimio član posade Expedition 62. Slika je obrezana i poboljšana za poboljšanje kontrasta, a artefakti leća su uklonjeni. Program međunarodne svemirske stanice podržava laboratorij u sklopu Nacionalnog laboratorija ISS-a kako bi astronautima pomogli da slikaju Zemlju koje će biti od najveće vrijednosti za znanstvenike i javnost, te da te slike budu slobodno dostupne na Internetu. |